Like so many people associated with the restaurant world, William Sitwell’s life changed beyond recognition when the pandemic hit last spring. One of the UK’s eminent food critics, he was left wondering what the future of the restaurant world would be, as well as looking back on how eating out has evolved over the decades and centuries that precede us.

William Sitwell: The History of Eating Out

Like so many people associated with the restaurant world, William Sitwell’s life changed beyond recognition when the pandemic hit last spring. One of the UK’s eminent food critics, he was left wondering what the future of the restaurant world would be, as well as looking back on how eating out has evolved over the decades and centuries that precede us. With an award-winning career in food writing, a number of published books, William’s House Wines founder and with a few guest Master Chef appearances, Sitwell’s most recent book is The Restaurant; A History of Eating Out. Within its pages, he chronicles the fascinating history of one of our favourite pastimes – dining out – and the long journey from Ancient Roman taverns to molecular gastronomy. I had the opportunity to sit down with William (virtually, of course) and find out some of the pivotal moments that have shaped the ‘modern restaurant’ as we know it today.

It’s been a year since the pandemic hit, and of course hospitality has been one of the most affected industries. What do you think the significance of restaurants is in our society in general?

Over the years, restaurants have become a cornerstone of our culture, and you really can’t underestimate their importance in society. They touch us on so many different levels, from entertaining to feeding us, to being a way for individual countries to express themselves as a nation. And I think, COVID aside, Britain offers a wonderful example of the breadth and depth restaurants can have. The different cuisines that are represented and different budgets that are catered for shows that British people are incredibly accepting when it comes to welcoming immigrant food and diversity, because we have unbelievable appetite for variety in all shapes and forms.

Our food and restaurant culture is a badge of identity, and the broader it is the more interesting that identity is. Restaurants are a huge employer in the UK: Nine million jobs are connected to the hospitality sector, so they’re important economically as well as culturally. Beyond this though, it’s important to remember they’re here to be enjoyed. It’s about being fed, being looked after, not always some frivolous luxury. Fish and chips provide the same function as a posh restaurant in the city: relaxation and switching off. I could chat about the importance of restaurants forever, the pleasure and fun they provide, which is why I’m so worried at the moment about the threat they face.

Our food and restaurant culture is a badge of identity, and the broader it is the more interesting that identity is.

In your book “The History of Eating Out” you talk about the first historical records of restaurants in Pompeii and Ancient Rome. What’s changed over the centuries, and what’s stayed the same?

I think when you write historical narratives you really need something concrete, so I wasn’t about to go around speculating whether Neanderthals did the washing up together. The thing that’s so extraordinary about Pompeii is that information we have from 79AD the date the city was destroyed, then preserved in volcanic ash. It was frozen in time exactly as it was, so you don’t view it today with some historical lens. And what you discover is that the purpose of hospitality in these early days is exactly the same as it is now. In fact that word hospitality comes from the ancient word, hospitium, and it was a concept enshrined in Roman law. Travelling to and from Rome and to the furthest regions of the empire, you were expected to give and receive that spirit of hospitality.

Hospitality is always a transaction of sorts, but it was also a very sophisticated scene in ancient Pompeii. There are bars, there are hotels, there are small restaurants with rooms, little taverns and brothels. And I think if you and I were to wake up in Pompeii, we would not feel that it’s too unfamiliar. We would see people from different classes mixing in bars, living and gathering side by side. What’s also interesting is that archaeologists have revealed the rich and poor had similar diets, based on their skeletons and the state of their teeth. The rich may have worn gold, but they ate together cheek to jowl. And there were bars, where the middle classes from across the Roman empire would visit and eat out.

The tablecloth is not necessary for the consumption of food. Neither is a fork or spoon really. You don’t need manners just to eat, but those layers of sophistication are built around food, and became part of its theatre and enjoyment.

Interestingly though, when the empire declined hospitality in Europe seemed to disappear, and we don’t see anything we’d recognise as a restaurant in London until the 1400s.

Why do you think hospitality died out with the Roman Empire?

This is one of the great mysteries. A lack of imagination, poverty, and maybe it’s the case that people tend to open restaurants in times of hope and prosperity. There were taverns and small time pubs in the Middle Ages, but we didn’t see things develop into what we’d call a modern ‘restaurant’ until 18th century Paris and London, really. The French revolution was an extraordinary moment for restaurants, actually, and by the end of the eighteenth century there were nearly 500 restaurants in Paris. Crudely speaking, this is because the revolutionists chopped the heads off all the aristocrats. The servants needed to work, so they went to the cities and they did what they could, they cooked food, they served, and often you find that they open small restaurants in the houses where they’d lived with aristocrats. It’s not the only reason for the growth of restaurants but it certainly contributed. Actually Paris took inspiration from London; one of the very first famous French restaurants in the 18 century was a place in Paris called La Grande Taverne de Londres, which in fact took inspiration from an establishment in London.

How about that story about the tablecloth? You mentioned in your book that it was the beginning of the ‘smart restaurant’.

Well, in that particular chapter on Medieval England I’m searching for some very early roots of smart dining. There is a mention of a tablecloth being unfolded in a place in Westminster in a poem from 1410 called London Lickpenny. You might think that I’m clutching at straws, but what’s interesting is that parliament at that time was evolving in Westminster as democracy was in its infancy. And were there regular parliaments, meetings and debating, a growing sophistication and the beginnings of administration and bureaucracy. So a whole middle class of professionals and lawyers was born, who wanted to hang around somewhere slightly smarter, somewhere that catered to them. So that poem you mentioned, with the unfurling of the table cloth, that’s the first mention that I can find about the tablecloth in English literature. It just gives you the inkling of the fact that there was something smart going on in 1410.

The tablecloth is not necessary for the consumption of food. Neither is a fork or spoon really. You don’t need manners just to eat, but those layers of sophistication are built around food, and became part of its theatre and enjoyment. A history of restaurants is also a history of etiquette, of the sophistication of society. There are many unnecessary things that we don’t actually need but become fundamental.

in the UK the industrial revolution was when we saw huge masses of people traveling away from home in order to work. Some would just stay for lunch, some would stay, and when you’re staying away from home you tended to see hospitality cropping up in these places. Eating away gradually became eating out, and it became a necessity but also a pleasure to have that pint of ale in a tavern.

Now, in some ways, we’re going back to being Neanderthals, because of the fast food we eat we don’t need cutlery but just our hands. But we all know how important it is to sit around a table eating and behaving; it’s civilization. If you can deal with cultural arguments around the table, if you can dine in a civilized fashion and entertain your colleagues, your friends, your guests, then you have the half chance to have a peaceful society. So actually that etiquette is more important than people think, it’s about convening in a safe, polite, civilized space. The more we can break bread with our friends and even our enemies around the table in a civilized way, the more the world has a chance for dialogue and peace. There is a reason why politicians at summits convene for dinner after a day of negotiating; they sit around the table and have dinner and the mood changes and conversation changes. The sip of wine, the taste of the food, brings different reactions to people.

You were also talking about coffee houses. That’s where the first debates happened and the first intellectuals were meeting in Europe. Right?

Absolutely. There were Roman emperors who were trying to ban people meeting in taverns because they thought that sedition would be cultivated. Charles II tried to shut down coffee houses too, because he worried about gossip turning into discontent, to political upheaval and so on. Similarly there were chocolate houses, where the people would meet and discuss completely frivolous things.

There is a famous quote by A. A. Gill, “What people go out to restaurants for is a good time —not because they are hungry.”. How did eating become more about pleasure than survival?

It’s really tricky to pin this down, but I think people have been eating for pleasure for a very long time. Samuel Johnson talks about the fact that there is no greater pleasure that can be had or found than in an inn. I can’t speak globally here, but in the UK the industrial revolution was when we saw huge masses of people traveling away from home in order to work. Some would just stay for lunch, some would stay, and when you’re staying away from home you tended to see hospitality cropping up in these places. Eating away gradually became eating out, and it became a necessity but also a pleasure to have that pint of ale in a tavern.

Certainly the 20th century has seen a revolution in eating out across the world. As international travel emerged, as logistics improved, as ingredients were able to arrive very quickly and between nations, there became this great variety of food. The Millennial generation eats out far more than our grandfathers certainly did. So there is now a greater offering of food for pleasure. But, frankly, for as long as we have had tastebuds food has been a pleasure, even if that just means a moment of brief enjoyment eating a fresh juicy berry while hiding from a sabre-toothed tiger.

But sincerely I’d say for the general public eating out for pure pleasure is really something that’s happened in the past 50 years. And certainly, we see a massive increase in hospitality as leisure during the last 20 years. People are traveling to countries to eat, going from London to Paris for lunch, flying to Copenhagen for dinner at Noma, even to New York sometimes, and this wasn’t happening until relatively recently.

You have the whole chapter about Ibn Battuta, the first “foodie” who was traveling for food. Can you tell us a bit about this?

I had a bit of fun there. Ibn Battuta took a gap year in 1325. And returned about 30 years later. He wrote about it in such detail about his travels from North Africa to China. He relied on the hospitality of strangers, and he was eating out for nearly 8 years. It showed great insight to the food that was available in the Old World of the 14th century. He sheds light on different civilizations: there were some people who provided him with food, and some people treated him as food and wanted to eat him. It was an extraordinary time in history.

Who do you think are the most important personalities that shaped the history of gastronomy?

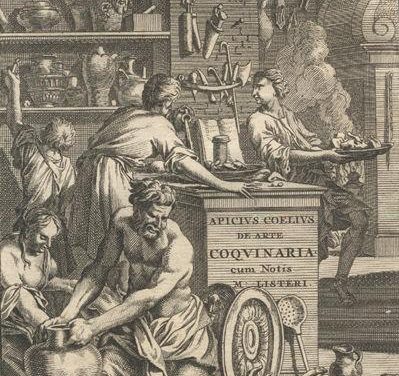

Well, historically, it’s a very difficult question… If you ask me my favorite chefs in history, I would say Marcus Gavius Apicius in the Roman Empire. His book is still in print two thousand years later, and he is a man who mastered the art of sauce. You can tell when the Roman Empire was at its greatest because the sauces were at their thickest and most sophisticated. Apicius was a tremendous foodie. He spent all his money on food, and when he eventually bankrupted himself he invited his friends to a banquet and poisoned himself during desert. He thought ‘If I can’t afford food, I would rather die,’ so he’s a hero of mine.

If we come up much closer in time, certainly The Roux brothers (both of whom have sadly died in the last twelve months) had a huge influence in the development of food in Britain after the war. It was a bleak grey period, and at the end of the Sixties these boys turned up. They saw an opportunity, because the food in London was so awful, and they were very excited about this. They were getting awful dinners in London. Their wives couldn’t believe it, asking: “Why are you so happy while eating such terrible food?”. They saw an opportunity to start something new, and they inspired chefs to see food and service as a profession.

In the United States, Alice Waters was hugely influential. She battled against the rise of US fast food culture in the early 70s. She connected diners with farmers. She tried to cut out the traders between them. And she built relationships with those farmers, she nurtured producers, she put their names on her menu. This was at the time of great American counterculture, anti-establishments, anti-Vietnam demonstrations. Artists, photographers and writers wanted her to meet. She also was a great entertainer, she was such a great cook, most of her friends persuaded her to open a restaurant. And among all fast-food, burgers and tacos, came this simplicity. There are so many pivotal figures around the world, but these are who I admire the most.

What are your few favorite restaurants in London?

Umu is a Japanese place that does amazing Kaiseki cuisine.

For classic British food I love Jeremy Lee’s cooking at Quo Vadis.

Any pub that Henry Harris is running, because he is one of the best chefs and restaurateurs for bistro cooking.

I have a friend in town, I would bring them to Chelsea Arts Club, because again, it’s about conviviality, it’s about a good time, and I know I will always have fun there around the big table.

It depends on one’s mood… Atul Kochhar has a fantastic Indian restaurant called Kanishka in Mayfair, it’s probably my favorite. It has a chicken tikka pie which is just amazing.

The best place for grilled meat I would say is Blacklock. They’re all about chops – lamb chops, beef chops, pork chops.