Art historian Rossella Menegazzo, Professor of East Asian Art History and the co-author of WA: The Essence of Japanese Design joins us on Luxeat to talk about the reason we’re so drawn to the simple, clean and minimalist designs we associate with Japan.

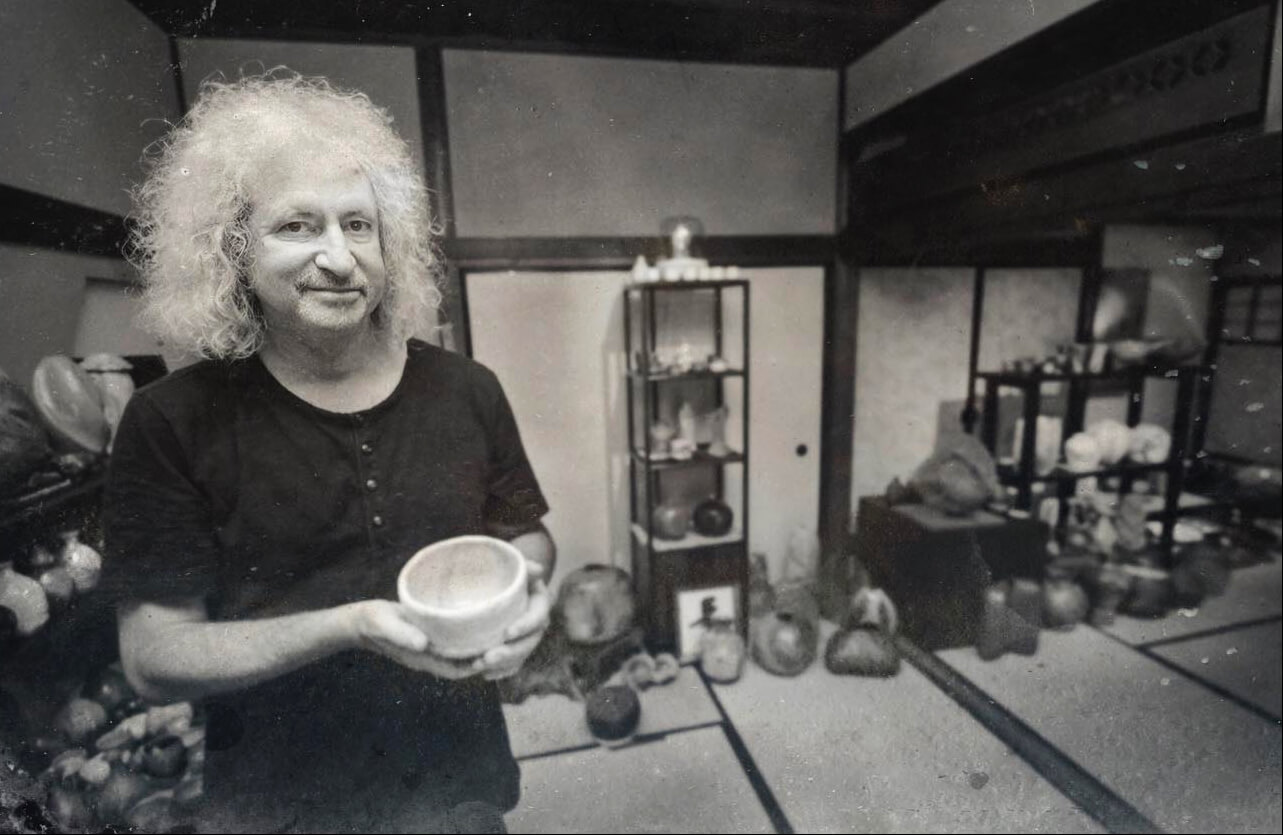

Japanese Ceramics with Robert Yellin

As part of our deep dive into Japan, Luxeat has the joy of meeting with a Japanese ceramics legend to better understand the history and importance of cups, plates and bowls across the nation. Robert Yellin is an American Japanese ceramics specialist who has been living in Japan since 1984. With ceramics’ roots in the sacred and quintessentially Japanese tea ceremony rituals, Yellin believes that it crosses the boundaries between art and functionality in Japan and enters into a Divine world.

How did you fall in love with Japanese ceramics?

Anyone who comes to visit Japan will discover little wonders and delights everywhere, but this is never more true than at the dining table. When people from the west, myself included, first come to Japan they often expect to find a complete set of matching plates. But when you look at the Japanese table you’ll discover myriad odd shapes, mismatching rustic and rough stoneware, elegant porcelain, which is totally unlike anything we’re used to. So that was my first introduction to ceramics; I love eating and drinking. There is such a deep culture around all the traditional crafts here – wood, metal, lacquer, glass, weaving – but one of the things I use most in my daily life is a teacup. It’s with me at breakfast, lunch time and dinner time providing me not only with the nourishment for my body, but also for my soul and for my spirit, because they are made of the elements of life itself, water, air, fire and clay, and they are made by potters whose conciseness you can basically hold and feel. So I started getting curious about Japanese ceramicists and the connection to Japanese history and culture and that was it.

How did you end up in Kyoto?

I originally opened my gallery in a small town called Mishima, Shizuoka prefecture. It was the late nineties and the internet was in its infancy, I made a webpage and started to connect with people all around the world. So anyway, Kyoto was always calling to me, the history, the culture, and the location, most of the wonderful old kilns in Japan are west of Nagoya. So it made sense for me to be in a location where I could access artists more easily than in Mishma. And then we found an amazing home/gallery, packed our bags and came down to Kyoto.

I think without the tea ceremony and its identity as one aspect of Japanese culture, you would not see the variety of ceramics we have today.

Why are Japanese ceramics so special? There are wonderful ceramics around the world, but Japanese are really different and there are many big Japanese ceramics fans and collectors around the world.

There are. I think one big answer to that question is the way ceramics have been immersed, not only into daily life, but with seasons and most particularly with the tea ceremony. I think without the tea ceremony and its identity as one aspect of Japanese culture, you would not see the variety of ceramics we have today. It’s also very spiritual as the old saying goes Tea equals Zen and Zen equals Tea. Of course, there are folk craft kilns which have nothing to do with the tea ceremony, who just make sturdy wares for daily life – vessels made to serve food, pour soy sauce, store grains or rice or whatever. Japan is such a mountainous country, so each regional tradition was very isolated and as a result is very distinct. Each region has its own style – not only with pottery but also cuisine, language, and utsuwa-vessels used in daily life.

So you would say that the tea ceremony was a very important factor in shaping Japanese ceramics?

Yes, absolutely. Many plates and dishes you find at kaiseki meals originated in the tea ceremony. From soy sauce pourers to chopsticks rests, various cups that hold tasty tidbits, those came from a tea ceremony meal. I think that it is the basic foundation of a variety of high-end functional ceramics that you find in Japan. Of course nowadays there is incredible ceramic sculptural art as well.

Historically, Japanese women were not given an opportunity to progress in society. They were expected to become housewives, and to study the tea ceremony and flower arranging and bring these into the home. And then of course after WW2, society changed. The elderly tea ceremony teacher has few students interested to take over the knowledge, so that tradition is in peril, and that has rippling effects across all craft traditions. Ceramics today are of course traditional yet as I just noted also very sculptural, dynamic, a focus for the international world, which is what many collectors look for today.

If you take your cup into a quiet place where it becomes a symbol and a metaphor then it will become a piece of art for you, art which you can hold and deeply ponder in the moment.

When does the vessel from which we drink become a piece of art?

When you take it from a kitchen, which is a sacred space in and of itself, to a place of quiet contemplation. You know, lots of conversations go in the kitchen, but if you take your cup into a quiet place where it becomes a symbol and a metaphor then it will become a piece of art for you, art which you can hold and deeply ponder in the moment. Not every cup, of course, can become a piece of art. There are some craftsmen who make the same form, the same weight, the same everything, and that’s craft, that’s artisanship. But a unique piece for me is a piece of art that was blessed by fire. Jewellery is very similar in this way, pottery is a sort of clay jewel from a kiln which was baptised with fire.

And crucially there is no reason art shouldn’t be functional. For most people art is hanging on their walls to impress, or maybe to inspire, but art should also bring some kind of functionality into your life, too. What’s nice about ceramics is that you can hold some, you can put food, flowers, tea, sake,etc..in them. It may give you dreams, it may calm you, it may excite you, and it may be there to provide something for you. Art should never be a commodity, that’s where people go wrong. “Prices are going to increase, how can I sell it if I want to sell it?”. In that case you should not collect art, you should buy stocks.

You have traveled around Japan looking for artists. What makes an artist special for you, what draws your attention when you see a piece of ceramics?

It’s intuition, it’s like a light bulb or a quiet tap on your heart. When it’s a light bulb I want to say, “woooow, what is that? That speaks to me!”, and when it’s a gentle tap on my heart it’s like, “hey, I’m here in the corner”. I used to go to lots of exhibitions in Tokyo when I was living closer to Tokyo, and there are few galleries which have interesting work. When I was teaching English in one of the universities, what is nice about these jobs is that you have half of the year off. So I was basically teaching half of the year and then another half driving around just looking at pots, going to bookstores and just looking, looking, looking.

Back then there was a company publishing books like “500 photos of teacups” or “500 photos of rice bowls”. I’d look at these books and if I liked something, I’d just give the artist a call. This was in the 80s, they were saying “Who are you, no foreigners can understand Japanese pottery!” But this is how we created relationships. And now I discover work in all sorts of ways, perhaps by introduction, or the artist calls me, or I go and just walk around town and stumble upon something, or I see a piece in a magazine or go to an exhibition… this is what Japanese call “de-ai,” a fortuitous encounter. The idea is that every day is an open new book of your life, it’s a blank page if you don’t have a routine. And even if you do have a routine you can, hopefully, find mindfulness in the present moment holding a ceramic piece connected to the past, rooted in the present, inspiring the future.

Ceramics today are of course traditional also very sculptural, dynamic, a focus for the international world, which is what many collectors look for today.

What makes a National Living Treasure?

The system was set up in the 1950s, when there was a big revitalisation and a lot of public attention to these ancient styles in many genres. It recognizes leading artists in designated fields as “bearers of intangible cultural properties”. In other words, you have to rise up from your region to become an icon on a national level. So you have to serve certain communities, you have to be a member of certain associations. It’s an incredibly important designation for any artist, and it’s not only in ceramics of course, it’s for many many different genres. It’s also important for that particular genre, because it focuses attention nationally, and it’s important as a citizen who might be interested in culture to go see these exhibitions. Just over 370 people have been given this title since it was created, and 111 of them are still alive today. Some of them, such as the Shino sake cup made by Arakawa Toyozo(1894-1985) I’m holding, are a way of holding onto and bringing traditions into the present. Arakawa had a few apprentices now famous in their own right and also inspired many, his legacy lives on.

For this first wave of national treasures, they actually had to research and dig into history, clay and figure out how to bring back the beauty of Momoyama period ceramics and make it their own. These people were dirt poor for a large part of their life, but they realized the significance of their respective styles, the Miwa family for Hagi style pottery, the Kaneshige family for Bizen, Arakawa for Shino, Black Seto and Yellow Seto, Ishiguro Munemaro for iron glazes, these people brought the beauty of ancient Japanese pottery and made it contemporary.

Actually, I was speaking today with Bizen’s current LNT Isezaki Jun. He’s a very humble person, there is no air about him, and he has four apprentices now. They started learning the basics, like for any chef when you walk into the kitchen, you’re washing floors and scrubbing pots. So these apprentices basically prepare the clay, a time consuming work, yet all important work where they learn about ingredients. It’s an honour to see and hold the work of Living National Treasures.

Finally, can you tell us more about your gallery?

It’s a traditional house built in 1935 and we have a traditional naka-niwa – an inside garden. On one side of the house there is a tatami room with a hearth for a tea kettle. I always say the gallery is not about me. I’m just a little window looking out to a fascinating world I’d like to share.. When people come to my gallery I want it to be an enjoyable learning discovery. Nothing is labeled; pieces have prices on the base, but people don’t see them. I want to see what is silently and intuitively communicated. And then they say Robert, tell me about that piece, and we have a discussion. And sometimes a work will be sent to the visitor upon their return home, yet the most important thing is that they see how important Japanese ceramics are to this very unique and inspiring culture.

Robert Yellin Yakimono Gallery